It is often an on-again, off-again disease, frightening in part because it is so unpredictable. It can defy conventional wisdom about adherence and early treatment. And escalating prices have undermined the cost-effectiveness arguments for the drugs that can keep it in check. Multiple sclerosis is a nightmare for managed care.

There’s no cure for the disease, the likelihood of disability is almost certain, and the cost of essential drugs continues to soar. It’s the kind of clinical and financial vise that grips the hundreds of thousands of Americans living with multiple sclerosis and, to some extent, the insurance companies and employers who foot the bill.

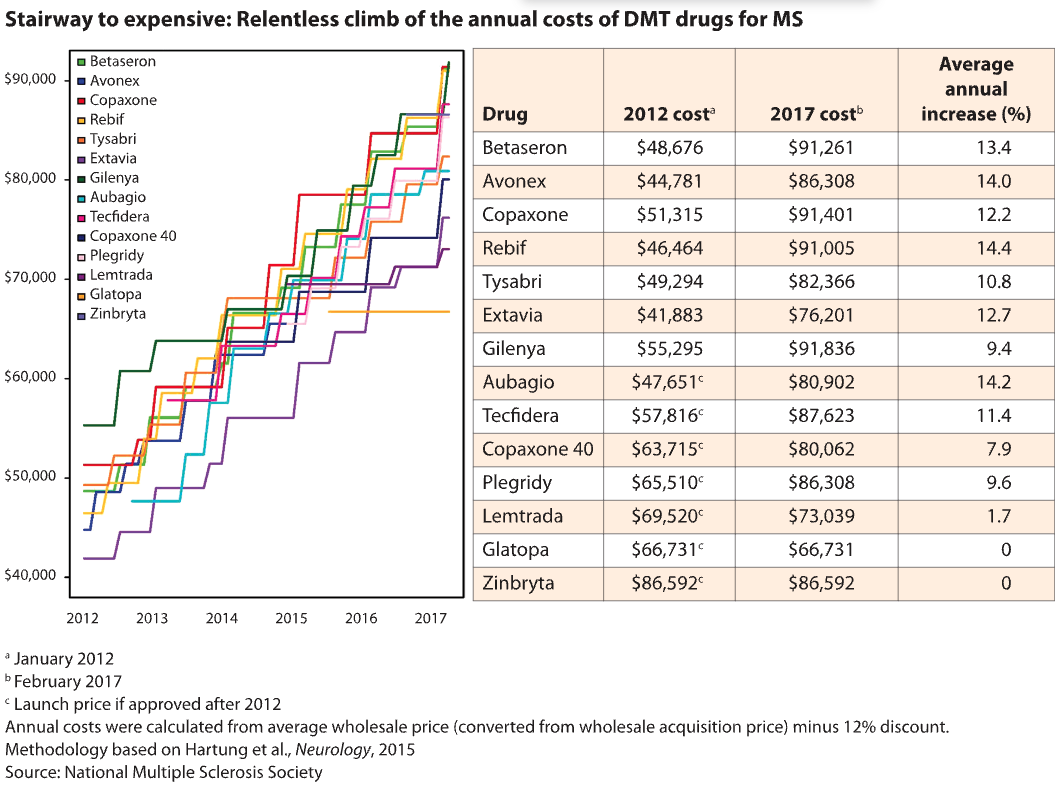

Despite the many drug options for MS – more than a dozen have been approved to treat the most common form – competition hasn’t kept a lid on prices. On the contrary, according to a widely cited pricing analysis published in 2015 in the journal Neurology.

Since the first wave of MS drugs were introduced in the 1990s at prices ranging from $8,292 to $11,532 a year, their costs have skyrocketed by as much as 36% year after year, according to the Neurology study. (During the same period, the overall inflation rate for prescription drugs was 3% to 5% per year). And newer drugs have kept pace. Nearly all MS drugs now cost between about $63,000 and nearly $104,000 a year, according to an analysis published last year by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER).

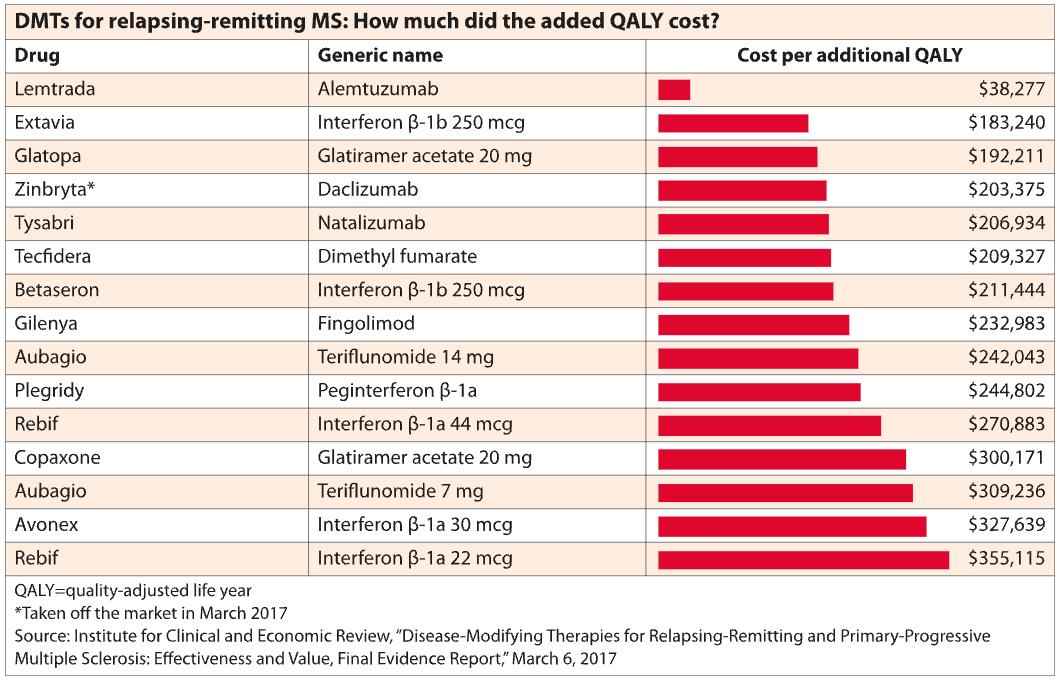

The price hikes have undermined the cost-effectiveness of these drugs, which treat a debilitating central nervous system disease with an inherently unpredictable course. At these prices, paying for the drugs year after year far exceeds the cost of caring for a patient after a relapse, researchers and prescription benefit managers say. Existing prices would have to be reduced by 37% to 98% to meet a cost-effectiveness benchmark of spending $100,000 to $150,000 for each additional quality-adjusted life year (QALY), according to the ICER analysis.

Payers continue to foot the bill for ethical, legal and contractual reasons, but “it’s really hard to make an economic argument,” says Gary Owens, MD, a biotechnology consultant in Ocean View, Del. who has written extensively on MS cost trends. “For the individual patient, the ability to remain functional and to drive, to be a parent, to go to work – all of that is a cost benefit to the individual. But the payers don’t get any of that benefit.”

“When the drug costs $5,000 or $6,000 a month, 30% is a substantial amount to pay out of pocket that patients face,” says Daniel Hartung of Oregon State University.

Meanwhile, patients covered by insurance policies that have high deductibles or require patients to pay a percentage of a drug’s cost are increasingly at risk of not being able to afford the drug at all, says Daniel Hartung, lead author of the 2015 Neurology pricing study and associate professor of pharmacy at Oregon State University College of Pharmacy in Corvallis.

“Patients are seeing higher and higher co-insurance, 28% to 30% co-insurance,” Hartung says. “If the drug costs $5,000 or $6,000 a month, 30% is a significant out-of-pocket amount that patients are facing.”

Fear of costs

The outcry over high drug prices is now part of the soundtrack of what ails American health care. But the furore over the cost of MS drugs highlights some of the challenges specific to autoimmune diseases.

It is not immediately a matter of life and death, as it can be for cancer patients. But once patients are diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and many other autoimmune diseases, they have to figure out how to pay for treatment that’s likely to be lifelong, with few options beyond taking drugs. A study published in 2013 found that medications accounted for two-thirds of the cost of medical care for people with MS. A more recent analysis by Prime Therapeutics, the PBM, reported that the drug bill was nearly 81% of total medical costs.

The MS drugs in question are called disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) because they’re designed to reduce or shorten relapses. Relapses occur when inflammation in the central nervous system damages the protective sheath around nerve fibres, causing symptoms such as weakness in the legs or loss of vision. Other, less expensive drugs, such as steroids, can help to relieve symptoms during a relapse.

Nearly all DMTs are approved for the relapsing-remitting form of MS, which affects more than 80% of MS patients and is characterised by relapses followed by periods of recovery. Last year, the FDA approved Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), which was launched at a price of about $65,000 a year. The infused drug, which can be prescribed for relapsing-remitting MS, is also the first approved to treat another category of MS, primary progressive disease, which develops in 15% of patients. MS patients with primary progressive disease experience worsening symptoms, often without breaks or remissions.

Cost just adds to the challenge of keeping patients on DMTs, along with the side effects and efficacy questions, says Bari Talente of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

PBMs are under fire these days for a lack of transparency about manufacturer rebates and other discounts. But they are trying measures to at least partially shield payers from high MS prices.

This year, Express Scripts launched a programme that reimburses payers for up to half of what they’ve already spent on a DMT if the patient stops taking it within the first three months. The MS programme, which requires the drugs to be filled through Express Scripts’ specialty pharmacy, also provides support for patients during those first few months, including education about potential side effects.

According to the PBM, about a quarter of patients discontinue their medication in the first few months. “If 25% of new patients discontinue therapy, that’s a lot of waste that plan sponsors are paying for that we know doesn’t benefit patients,” says Harold Carter, senior director of clinical solutions at Express Scripts.

This summer, CVS Health announced a programme that would allow any of its payer clients to exclude a newly launched drug – outside of “breakthrough” drugs – that costs more than $100,000 per QALY, according to ICER’s analysis.

Owens questioned whether CVS Health’s move would provide much relief to payers, given that nearly all existing MS drugs far exceed this QALY benchmark. “I don’t think any payer or employer is going to say, ‘Well, these drugs are not cost-effective, so we’re not going to pay for the treatment of MS patients.'”

Economics of adherence

ICER’s analysis also highlighted some gaps in what’s known about DMTs – starting with the limited time frame of clinical trials, typically one to two years. While this trial length is not uncommon, it makes it particularly difficult to assess the benefits and harms of a drug for a disease that progresses over decades, says Dan Ollendorf, ICER’s chief scientific officer.

Ollendorf cites another major knowledge gap: Little research has looked at the optimal sequence for these drugs. For example, he says, “to understand whether patients do better if they start with an interferon and then move on to something more targeted, or vice versa”.

In guidelines released earlier this year, AAN leaders didn’t recommend any specific drugs over others for relapsing-remitting MS. (One exception: They suggested a short list of drugs – Lemtrada [alemtuzumab], Gilenya [fingolimod] and Tysabri [natalizumab] – for patients with signs of highly active MS.) Instead, the expert group provided a consumer-friendly summary of the drugs in alphabetical order, with details of their side effects, method of administration and strength of evidence for relapse prevention.

In contrast, ICER tried to rank the drugs according to their clinical effectiveness. Lemtrada, Tysabri and Ocrevus were identified as most likely to reduce relapses, followed by other drugs based on their relative effectiveness. But will this ICER guidance influence payers’ decisions? At this point, with all the drugs costing roughly the same and no standout options, payers will be more influenced by discounts and rebates in choosing their preferred drug options, says Hartung, the author of the Neurology pricing study. Manufacturers try to make the case that payers will reduce other MS-related costs by spending money on drugs, says Owens. But the reality is that the worsening of the disease, even as disability progresses, is not terribly costly from a payer perspective, he says. A patient might be hospitalised for a short time in the event of a severe relapse. Other expenses include low-cost drugs such as steroids and the purchase of a wheelchair or other medical equipment.

Manufacturers try to make the case that payers will reduce other MS-related costs by spending money on drugs, says Owens. But the reality is that the worsening of the disease, even as disability progresses, is not terribly costly from a payer perspective, he says. A patient might be hospitalised for a short time in the event of a severe relapse. Other expenses include low-cost drugs such as steroids and the purchase of a wheelchair or other medical equipment.

Patients can still relapse even when they’re faithfully adherent to DMTs, and that can be very costly, says Patrick Gleason of Prime Therapeutics.

In addition, patients can relapse even when taking one of the DMTs faithfully, according to a cost-effectiveness analysis by Prime Therapeutics, which looked at relapses in 991 patients. During the three-year period analysed by Prime, 18.2% of adherent patients relapsed, compared with 24.9% of those who weren’t adherent. The medical bill for a relapse was nearly $9,000, according to an abstract presented at a meeting earlier this year.

The bottom line: Medication adherence would need to be improved for 15 patients over three years – at a cost of about $3 million – to prevent a single $9,000 relapse. These findings are consistent with ICER’s recent cost-effectiveness analysis for MS, notes Patrick Gleason, senior director of health outcomes at Prime Therapeutics. “Our results are somewhat consistent with that – the value is hard to see,” he says.

Payers have responded to rising prices by limiting the number of MS drugs on their preferred lists, with only a few options, often including an interferon and an oral medication, says Owens. Otherwise, patients and their physicians must navigate prior authorisations and other plan designs, such as a step therapy approach that requires patients to “fail” on a preferred drug before trying another.

Dan Ford blames prior authorisation hurdles for further and potentially avoidable deterioration of his disease. When the military veteran was diagnosed with MS three years ago at the age of 49, his neurologist in Kansas recommended that he start the infusion drug Tysabri immediately because of the apparent severity of his disease, as indicated by his symptoms and two lesions already detected in his brain.

But it took almost three months – and a series of appeals to doctors – before Ford’s insurer agreed to cover the drug. By then, Ford was quite ill and weak and had to be hospitalised for several days. MRI scans showed that two more lesions had appeared on his spinal cord. He’s been largely wheelchair-bound ever since. No further lesions have appeared, he says.

“

The way I look at it, those second two lesions cost me my legs,” says Ford. “And put a price tag on that?”

In recent years, a generic option has entered the MS market. Two manufacturers – Mylan and Sandoz – market generic versions of Copaxone (glatiramer acetate). They are 20% cheaper than Copaxone, says Hartung. That helps, but it’s not a huge, game-changing difference. Typically, it takes four to six manufacturers before competition starts to drive costs down significantly, notes Hartung.

As they proliferate, however, generics could have an impact. In their 2015 Neurology pricing analysis, Hartung and colleagues speculate that prices for TNF inhibitors haven’t followed the same arms race price trajectory as MS drugs, perhaps in part because these drugs compete with methotrexate and other generics.

Has Ocrevus set a good example?

Bargaining power can also make a difference. At the Veterans Health Administration, which can negotiate prices, DMTs cost about a third less than what Medicaid pays, according to the 2015 Neurology analysis. In a campaign against high drug prices launched in 2016, the MS Society recommended that Medicare be given the same negotiating power. Some of its other proposals target payers and insurance design, including spreading patients’ out-of-pocket drug costs more evenly over the year and not putting all drugs on the same specialty tier.

“If you have all the available products on a specialty tier, which typically comes with co-insurance, you have no alternative,” says the MS Society’s Talente. “You need your medication.”

Talente was among those interviewed who pointed to Ocrevus – launched in 2017 at a wholesale acquisition cost nearly 20% below the market average for DMT drugs – as perhaps a small break in the pricing fever. “It was very encouraging – it shows that it can be done,” she says.

The drug could have been launched at a “premium price”, agrees Owens. The infused drug has many clinical strengths to promote, including that it’s the first approved for primary progressive MS and has been shown to be more effective than an interferon.

Perhaps Genentech’s pricing reflects a well-considered positioning strategy to try to grab a hefty market share right from the start, says Owens. Or it may, at least in part, reflect a manufacturer’s sensitivity to the current pricing environment, he says.

“This nuclear arms race in the ever-increasing cost of MS is putting us in a position that’s very difficult for the patient, the employer, the payer and even the manufacturer to justify,” says Owens. “You’d like to think they were listening.”

Some MS basics

The first long-term medications for multiple sclerosis were approved in the 1990s, but there are still gaps in what’s known about the drugs, and even about the course of the disease itself, which can vary from patient to patient.

How many Americans are diagnosed?

While it’s generally accepted that 400,000 Americans are living with MS, there is some dispute over this figure. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society, concerned that the number was out of date, launched a prevalence analysis. Based on the society’s preliminary findings, nearly one million US residents have the disease.

Which drug to start first?

According to the American Academy of Neurology, there’s no generally accepted guideline on this, or on which drug to switch to if the first one doesn’t work.

How do the medications compare?

There are few trials that compare one disease-modifying therapy with another, rather than just supportive care. But that’s starting to change with some of the newer drugs, such as Gilenya (fingolimod) and Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), which have both been tested head-to-head against an interferon.

Does a particular drug work?

According to the American Academy of Neurology, there’s currently no blood test to assess the effectiveness of a drug. Patients are monitored on the basis of symptoms and whether changes in the brain can be seen on an MRI.

So how do you decide which drug to take?

Doctors and patients usually decide together based on clinical evidence, insurance coverage, side effects and other medical conditions a patient may have. Another factor is how the medication is administered. For example, Copaxone (glatiramer acetate) is given by injection, whereas Gilenya is a pill, so some patients may prefer Gilenya.